I used Boston Marathon runners’ official smartwatch stats to help with my training

[ad_1]

When a major race like the Boston Marathon ends, most people only focus on the finish times. But pro athletes only hit these insane 2-hours-and-change times by being painstakingly exact with splits, running form, and other stats you get from a fitness watch.

So when COROS sent me its Pro runners’ Boston Marathon stats like per-mile heart rate, cadence, and effort pace, I knew I had a lot to learn from their approach!

You can’t compare your flag football stats against Patrick Mahomes or pickup basketball results against Steph Curry. But all runners are on the same playing field, aiming for the same distance.

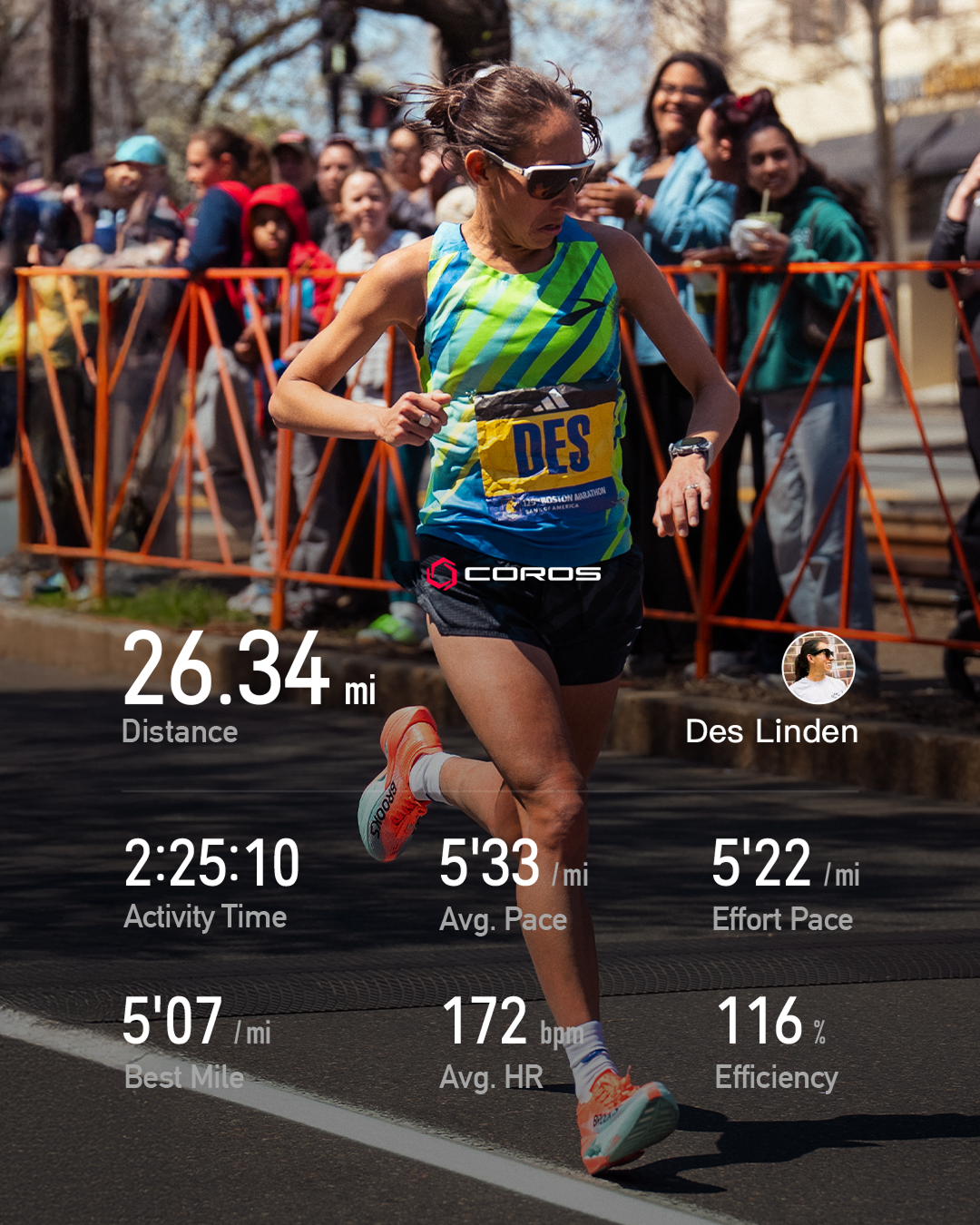

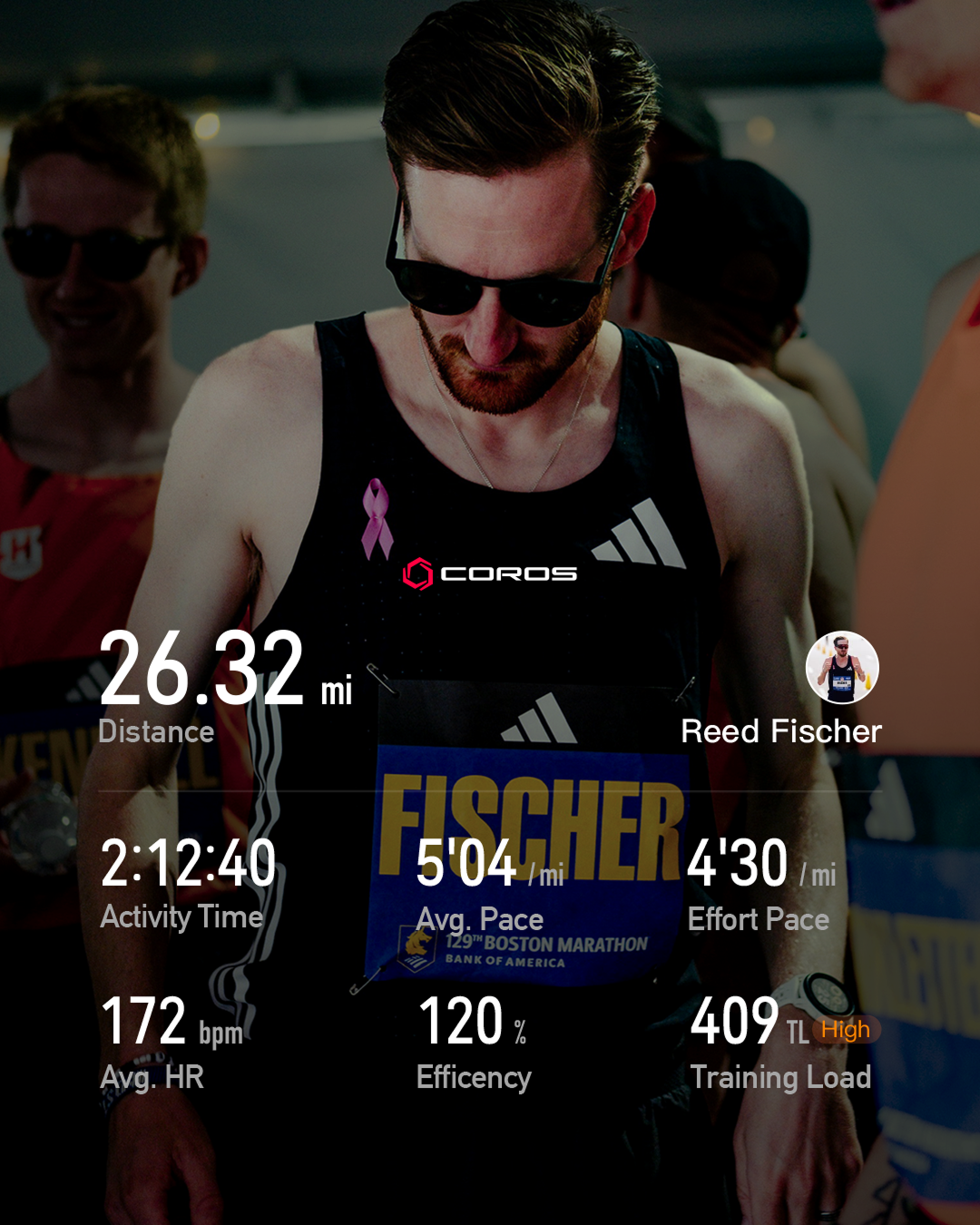

First, I picked through the runner summaries COROS sent for Yalemzerf Yehualaw (3rd place), Emma Bates (13th), Des Linden (17th), Charlie Sweeney (19th), and Reed Fischer (21st), all top-tier runners for one of the most famous races in the world.

All of COROS’ Boston Marathon team wore either the $349 COROS PACE Pro (Linden) or $229 COROS PACE 3 (Bates, Yalemzerf, Sweeney). It’s pretty cool knowing they use the same tools as everyday runners to analyze their own stats — and that you can directly compare your data against theirs to provide humbling context and insight.

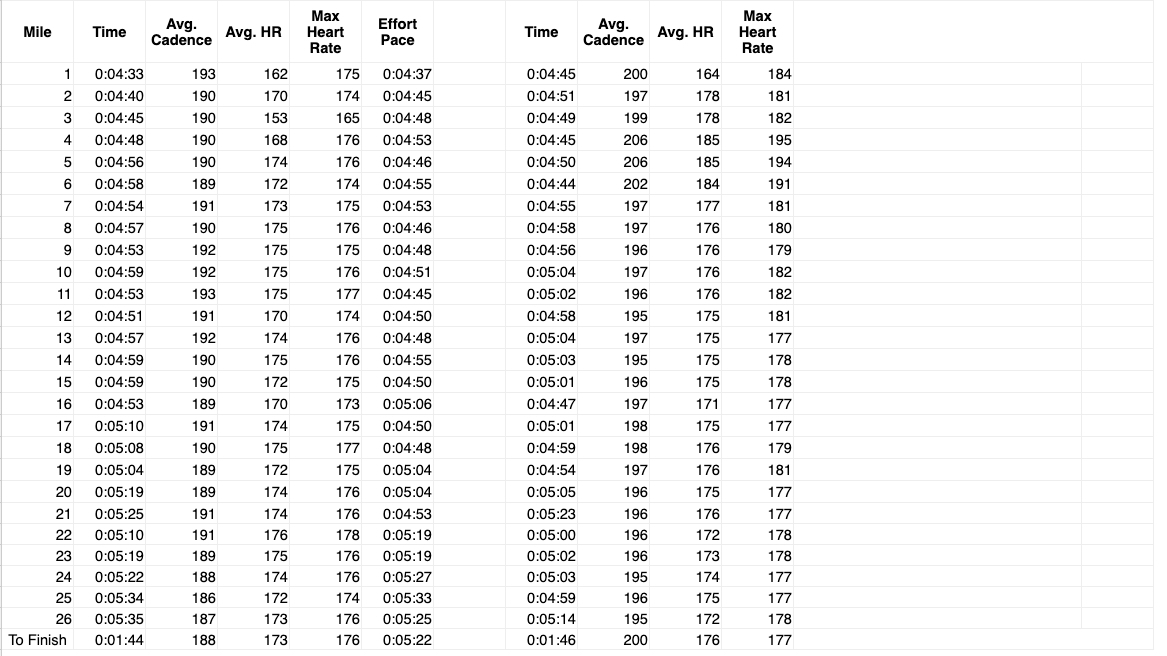

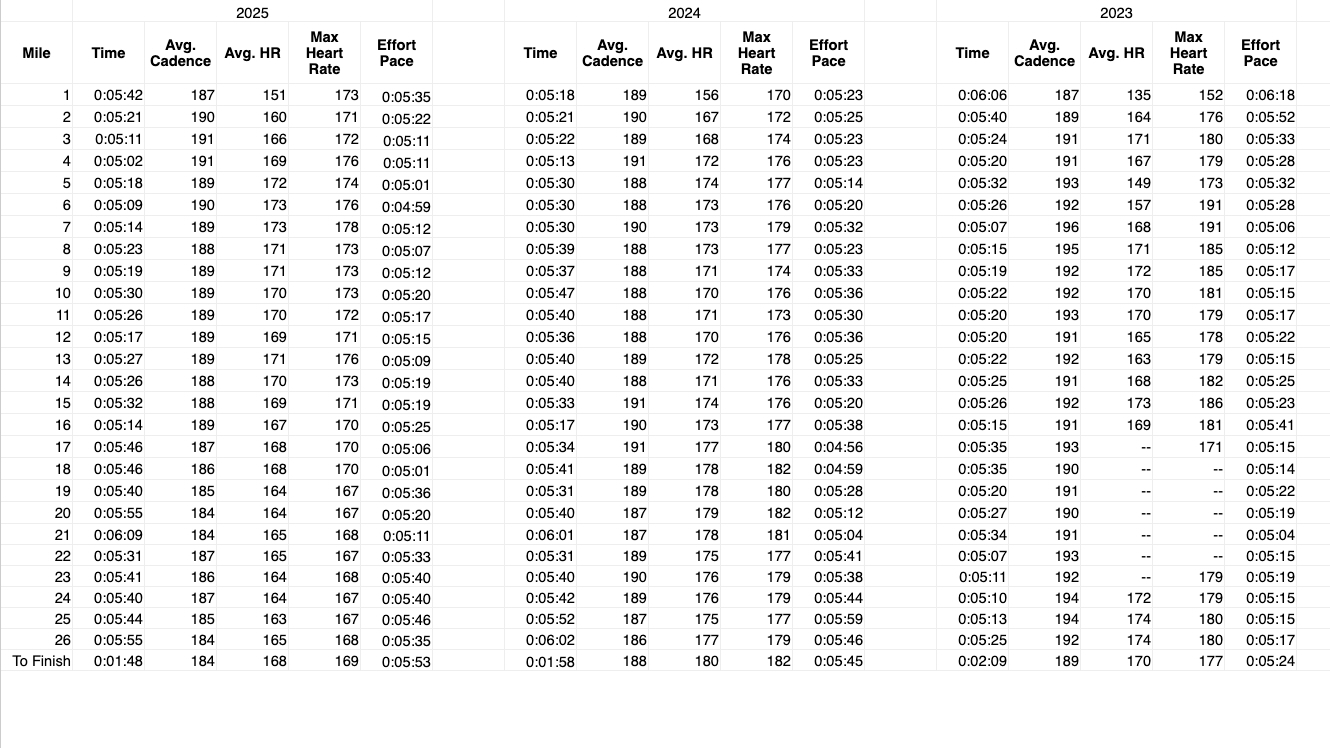

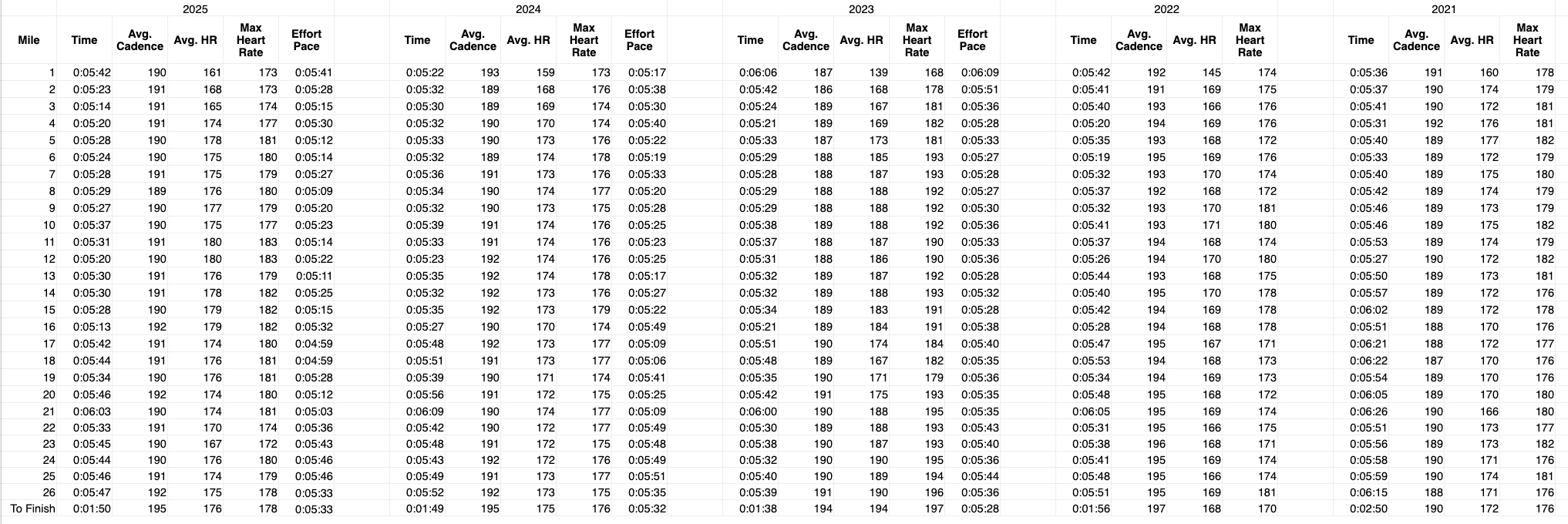

COROS was also kind enough to send a spreadsheet of per-mile stats for Bates, Fischer, and Linden for their pace, cadence, average/ max heart rate, and the changes from one mile to the next — or lack thereof — is fascinating and enlightening.

Here’s what I gleaned from looking through these pro runner stats!

Consistency is vital

From miles 2 through 16, Reed Fischer’s pace never changed by more than 6 seconds. And from mile 5 onwards, his average heart rate stayed in the same 170–176 range — while his average and max HR were almost always within 1–2 bpm.

Des Linden’s average cadence fell between 188–191 steps per minute for the entire race until the final 0.2-mile sprint to the finish. Even when her pace dipped and stride lost power, she kept the same speed of her form, and her per-mile pace was remarkably consistent even across elevation changes.

I don’t have Yehualaw’s per-mile stats, but it’s very telling that the gap between her fastest and average kilometer is only 20 seconds. And Linden, a role model for running longevity at 43, only had a 5-second gap between her mile-1 and mile-26 times, and a 33-second gap between her fastest and slowest mile.

These stats are a great reminder that you don’t want to let your fellow runners dictate your pace. Even when you’re in the zone and feeling great, you must restrain yourself, stick within your capabilities, and keep your heart pumping to the beat of a metronome.

You’re probably trying too hard

I don’t know these athletes’ actual max HRs or lactate thresholds, but the “220 minus age” estimate shows me that all these runners were probably running, on average, right at the border between Zone 4 and 5 for most of their run. That’s certainly not easy, but they rarely approach their max effort.

In fact, their heart rate tends to dip in the final miles; they ease off their pace to stick to what their bodies are capable of.

COROS has an “Effort Pace” metric that combines grade-adjusted pace (GAP) with your ability level to judge how hard you’re working to hit a pace and adjusting the speed accordingly. By and large, these runners’ effort pace was almost always lower than their real pace; they didn’t push harder than their usual abilities, even for the biggest race of the year.

Fischer’s first four miles did show a higher effort pace than actual pace, which I’d guess stems from him trying to stick with the faster leaders for the first 5K. Once he fell behind, his pace became more efficient and within his means.

Our goal, then, should be to keep at a similarly consistent heart rate and foot speed for our races rather than trying to outperform our capabilities and burn out in the later miles. If you want to go faster, build up your speed and endurance until you can naturally maintain a faster cadence.

There’s no shortcut for getting faster

I averaged about 25 spm fewer than Charley Sweeney (who is my height) in my recent half-marathon PR, or 14 spm fewer during a max-effort interval workout. That’s not a surprise or anything; just like when I tried to match Olympic paces on my local track, I know my running capabilities are firmly amateur.

But it did tempt me to consider whether I should try to change my running form to aim for faster step speed…until I remembered the time I asked Garmin Forerunner product manager Joe Heikes how to improve my running form. He basically warned me not to.

Any self-correction to change your natural form will lead to “less economical running,” Heikes said, and runners should instead use form data like cadence as a benchmark; the lighter, faster, and stronger you get, the less wasted movement and slow turnover you should see without any conscious changes.

If there is a way to improve your form, it’s with strength training to make your muscles capable of the extra impact. COROS coaches suggest burpees, mountain climbers, and other bodyweight jumps for faster ground contact time and lower-body exercises like squats, deadlifts, and calf/heel raises for a stronger stride.

The main point being, if I want to emulate these athletes’ foot speed, it’s arguably just as much about strength as endurance. These stats were a bit of a wake-up call to stop neglecting my cross-training.

Emulating their approach (only slower)

Plenty of amateur runners will look at these stats and get discouraged, knowing they couldn’t run one mile as fast as these athletes’ slowest Boston Marathon mile.

I look at it differently. I know that I can’t run that fast, obviously, but I can emulate their race tactics.

My per-mile efficiency or performance condition stats show the turning point when I have to start using more effort at a higher heart rate than I should; the goal is to push that point further back.

During a race, I need to practice consistent pace and heart rate habits. Rather than just sink into the zone and run at a pace that feels right until my legs give out, I can use my running watch data to stay at a pace I can manage, particularly in the early miles when it’s easy to get carried away.

[ad_2]

Source link