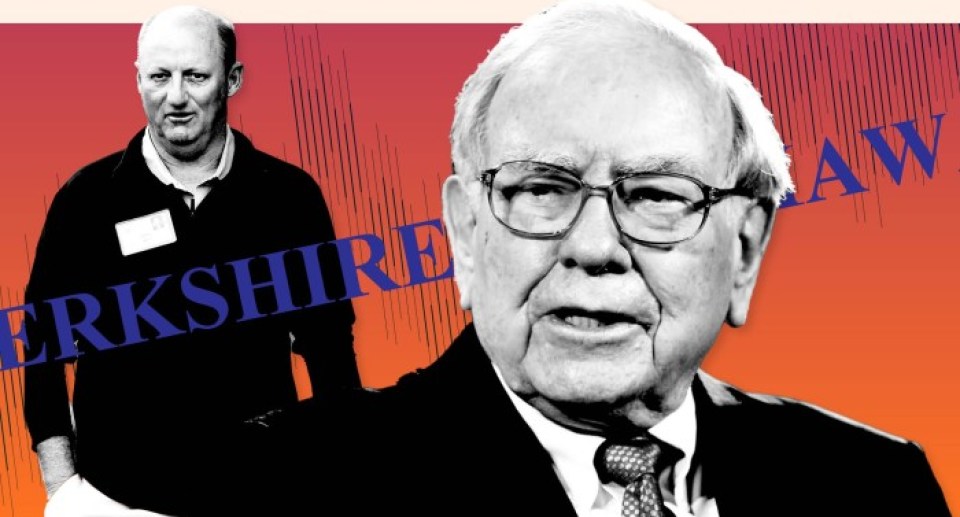

Greg Abel faces tricky task leading Berkshire Hathaway after Buffett

[ad_1]

As 40,000 Berkshire Hathaway shareholders took to their feet in Omaha on Saturday in a standing ovation for Warren Buffett, Greg Abel was among those applauding the career of the world’s greatest investor.

By the time they gather for next year’s annual meeting their eyes will be fixed on Abel, Buffett’s handpicked successor at the financial powerhouse he spent six decades building.

The 62-year-old, who rose up through Berkshire’s utility business, will be scrutinised in a way Buffett has largely avoided in recent years, with investors trusting in returns that have beaten the benchmark S&P 500 by more than 5.4mn per cent over the past 60 years.

The tasks for Abel are two-fold: maintain the culture that Buffett and his late vice-chair Charlie Munger instilled in Berkshire, while putting the group’s record war chest to work.

It will take investors years to know how Abel stacks up as a capital allocator, whether he will have the same talent at identifying where to move the billions of dollars that flow into Omaha each month, and if he can come close to matching Buffett’s returns.

“I think the bar for replacing Warren Buffett is an impossible one,” said Christopher Bloomstran, president of investment group and Berkshire shareholder Semper Augustus. “Greg will be under a microscope, not so much from the shareholder base but from the public eye.”

Some of America’s most powerful financiers saluted Buffett after his announcement on Saturday, a sign of his gravitas on Wall Street.

Jamie Dimon, chief executive of JPMorgan Chase, told the Financial Times that Buffett “represents everything that is good about American capitalism and America itself”, while Goldman Sachs boss David Solomon said the investor had “influenced a generation of leaders who have benefited from his unusual common sense and long-term approach”.

Yet such acclamation is a sign of the challenge facing Abel.

Berkshire has struggled for years to identify suitable acquisition targets. Buffett has said he and his team have already picked through anything worthwhile to buy, but that valuations are stretched.

That has at times flummoxed shareholders, who have watched as Berkshire lost out on takeovers to other bidders or sat on the sidelines. However, Buffett could ultimately be vindicated if a wave of leveraged buyouts in the aftermath of the pandemic, in which buyout firms paid sky-high prices, flounders under the weight of debt and a slowing economy.

There is also the risk that parts of Berkshire itself are targeted for takeovers. But Buffett’s high-vote class A shares, as well as Berkshire’s sheer size, has long warded off activists and the private equity industry, which could look to snap up any number of the company’s hundreds of subsidiaries. And the fact that the trust overseeing Buffett’s shares after his death will slowly donate them to charities means Abel is unlikely to face threats from outside investors any time soon.

Abel will have enormous firepower when he takes the reins: Berkshire is sitting on almost $350bn of cash after net sales of about $175bn in stocks over the past 10 quarters.

Buffett reminded investors on Saturday that Berkshire was often flush with opportunities during sell-offs. With the upheaval in the US economy, those could soon present themselves for Abel.

The question is whether he will be more aggressive in searching out targets or will be more plugged into the Wall Street dealmaking machine, which Buffett has largely avoided.

Buffett’s reputation was solidified by big calls such as sitting out the late 1990s dotcom boom, so avoiding the carnage when the bubble burst, and having cash ready to deploy during the global financial crisis, when he helped safeguard banks including Goldman Sachs by investing. More recently he slashed the company’s stock holdings, in part on valuation grounds. That raised questions for shareholders until recently, when the market’s correction and economic instability made the decision look prescient.

In time, Buffett said at the Saturday meeting, “we will be bombarded with offerings that we’ll be glad we have the cash for”. He added: “It would be a lot more fun if it were to happen tomorrow, but it’s very, very unlikely it will happen tomorrow.”

Whether Abel will be extended the same goodwill as his towering predecessor, and whether he can get to grips with all of Berkshire’s activities, remains to be seen. While he has been instrumental in a number of big acquisitions, including several energy businesses, he has not had oversight of the company’s $264bn stock portfolio — one of Berkshire’s crown jewels.

“He’s not known as an investor,” said Bill Stone, chief investment officer of longtime Berkshire shareholder Glenview Trust, adding that his confidence in Berkshire was based on his faith in Buffett as a trustworthy steward of investors’ money.

Larry Cunningham, George Washington University professor and author of Berkshire Beyond Buffett, said Abel’s commitment to Berkshire’s investment philosophy did not mean there would be no changes under his leadership.

“Abel is an operations guy, while Buffett has adopted a famously laissez-faire approach, trusting managers,” he said.

A more operationally savvy chief executive could bring benefits in helping Berkshire subsidiaries share ideas and expertise, Cunningham said, but it came with a risk: would sellers of businesses be as keen to be acquired by Berkshire?

“Abel was clear that he is committed to the principle of autonomy — he will not meddle,” Cunningham said. “But Buffett’s delegation made managers want to vindicate his trust. Abel will have to develop that superpower.”

Few expect Abel to take Buffett’s place in the investing firmament, or to develop the cultural cachet that drew millions of people to Buffett and his philosophy.

Howard Marks, co-founder of Oaktree Capital, believes it is impossible for anyone to measure up to Buffett, whom he described as “the single most influential investor of all time — the Isaac Newton of investing”.

“He says when he started in the early 1950s, he was able to buy dollars for 50 cents — and he makes it sound easy,” Marks said. “But the thing is, even if the opportunities were there, nobody else did it. There weren’t multiple Warren Buffetts.”

Additional reporting by James Fontanella-Khan

[ad_2]

Source link